Our Definition of "Hero" |

您所在的位置:网站首页 › reasons why we need heroes阅读 › Our Definition of "Hero" |

Our Definition of "Hero"

|

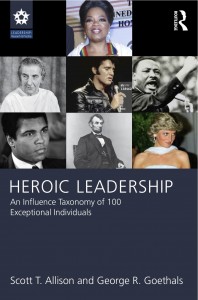

Most social scientists define heroism as exceptional pro-social behavior that is voluntary and involves risk and self-sacrifice. Although we respect that definition and recognize its value, we take a more subjective approach in defining a hero. If you haven’t read our first heroes book, our definition of a hero is based on our research on people’s stated choices of heroes. We’ve asked many hundreds of people to tell us who their heroes are, and why. From our data it’s pretty clear that heroism is in the eye of the beholder. Preferences for heroes are as varied as people’s taste in music, movies, and paintings. Defining a hero is like defining a good meal at a restaurant. It depends on your values, your personal experiences, and maybe even the current developmental stage of your life. Cancer victims name cancer survivors as their heroes. Soccer players list soccer stars as their heroes. In short, your needs and motives determine whom you choose as heroes. Maturity and development play a role in hero selection, with younger people tending to choose heroes known for their talents, physical skills, and celebrity status. Older people tend to favor moral heroes. As we get older and wiser, our tastes in heroes evolve. Some have suggested that with age and wisdom, our choice of heroes improves — perhaps as we get older we become more discriminating and more respectful of the term “hero”. The point we wish to make is that every person we have profiled in this blog is someone’s hero. We didn’t choose the heroes whom we profile on this blog — you did. Each hero may not be your personal hero, but he or she is somebody’s hero, and the reasons are valid and meaningful to the person holding them. Even Joseph Campbell, the great mythologist and founder of the study of heroes, acknowledged that heroism is in the eye of the beholder. Campbell said, “You could be a local god, but for the people whom that local god conquered, you could be the enemy. Whether you call someone a hero or a monster is all relative….” (The Power of Myth, p. 156). The World War II German soldier who died, said Campbell, “is as much a hero as the American soldier who was sent over there to kill him.” Campbell believed that the moral objective of heroism “is that of saving a people, saving a person, or supporting an idea.” Although we agree with Campbell, and others, that heroism is in the eye of the beholder, we will never profile people such as Adolf Hitler in our blog, even if Hitler is considered heroic to small segment of society. There are some people whose values are so repugnant to us, and to the reasonable majority, that we will never profile them here. We’ve found that people’s beliefs about heroes tend to follow a systematic pattern. After polling a number of people, we discovered that heroes are perceived to be highly moral, highly competent, or both. More specifically, heroes are believed to possess eight traits, which we call The Great Eight. As authors of this blog, we do have our own personal heroes. Our heroes combine great selflessness with great ability. In our second heroes book we call heroes of this type Traditional Heroes. One of us (Scott Allison) identifies Roberto Clemente his greatest hero. Clemente was a great baseball player who died helping earthquake victims. The other of us (George Goethals) calls Abraham Lincoln his greatest hero. Lincoln showed remarkable heroic leadership while healing a divided nation and freeing slaves. When we were younger, a person didn’t have to be particularly moral or selfless to be a hero to us. The person just had to be a star athlete or great rock star. We’ve outgrown this type of hero, which we call a Transitional Hero. Now our heroes have to accomplish far more than show great ability. They must also perform some exemplary action in the service of others. Our research has also found that there are at least 12 functions of heroism. Heroes give us hope, heroes energize us, heroes develop us, heroes heal us, heroes impart wisdom, heroes are role models for morality, heroes offer safety and protection, heroes give us positive emotions, heroes give us meaning and purpose, heroes provide social connection and reduce loneliness, heroes help individuals achieve personal goals, and heroes help society achieve societal goals. We will certainly continue to welcome any debates about the validity of our contentions in this blog. Critiques about the hero-worthiness of a particular individual may sharpen our thinking about who are the special men and women among us who deserve the term “hero” associated with their names. In the mean time, let’s honor the diversity of opinion out there about who our heroes are. We’re all in a different place in life, and our heroes shift and evolve as we ourselves shift and evolve. UPDATE June 2024 — We’ve recently published the Encyclopedia of Heroism Studies. In it, we describe our current thinking about the definition of heroism. References Allison, S. T. (Ed.) (2022). The 12 functions of heroes and heroism. Richmond: Palsgrove. Allison, S. T. (2023). Definitions and descriptions of heroism. In S. T. Allison, J. K. Beggan, and G. R. Goethals (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Heroism Studies. New York: Springer. Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2011). Heroes: What They Do & Why We Need Them. New York: Oxford University Press. Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2025). Heroic Leadership: An Influence Taxonomy of 100 Exceptional Individuals. New York: Routledge. Campbell, J. (1988). The Power of Myth. (with Bill Moyers). Share this:FacebookLinkedInTwitterLike this:Like Loading... |

【本文地址】

今日新闻 |

推荐新闻 |

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals These traits are smart, strong, resilient, selfless, caring, charismatic, reliable, and inspiring. It’s unusual for a hero to possess all eight of these characteristics, but most heroes have a majority of them.

These traits are smart, strong, resilient, selfless, caring, charismatic, reliable, and inspiring. It’s unusual for a hero to possess all eight of these characteristics, but most heroes have a majority of them.